Montgomery County Volunteer Fire Rescue Association wishes to thank Montgomery County History for allowing us to share the article. Please note the number of personnel and fire stations has only increased to date.

Text taken from “The Montgomery County Story,” Volume 46, Number 3 (2003) by Shannon Fleischer, published by Montgomery History”

Fire protection has been a recognized need in Montgomery County since the early 1800s, although there were not any formally organized volunteer or career fire departments until almost 100 years later. At first, citizens had to depend on family and neighbors to come running when flames broke out. As the population grew, communities began taking action to form groups of able-bodied boys and men, white and black, to be on call at a moment’s notice to assist in rescuing people, salvaging furniture, herding livestock and trying to get the fire under control so as not to bum the entire town.

Early groups used mostly private equipment – buckets, for one thing – in addition to some facilities and equipment provided by the towns. The early bucket brigades led to organized volunteer fire departments and later to hired firefighters. Finally, in order to adapt to the needs of the population and to make the best possible use of modem technology, there was county consolidation of the fire departments. This is the story of the history and development of today’s 33 individual fire departments within the Montgomery County Division of Fire and Rescue Services.

From its beginning in 1776, Montgomery County dealt with fire problems caused by lighting and heating practices that were common to their time but unsafe by today’s standards, and increases in population that created villages and towns where buildings were close to one another. Communities consisted mostly of merchant families, with farming families living on the edges of town or scattered throughout the countryside. These were the days when neighbors knew one another and depended on each other, which was especially true when fire struck a home. Whether it was an exploded lamp, a kitchen fire or a candle or lantern dropped or knocked over by wind, little could be done besides evacuate the family and try to salvage a few valuables.

At the first word of fire or the sight of smoke, it was expected that all able-bodied men and boys would come running with buckets in hand. Bucket brigades would form from wells or nearby streams, while others would be trying to get out as much as possible from the house or barn. It usually was not expected that the fire would be put out, but rather that it would be contained so that it did not take the house – or the whole town. This became difficult when water supplies were low or there were no wells nearby. As early as 1806 the Mal(land General Assembly authorized a lottery to purchase a fire engine for Rockville. It consisted of a hand-drawn barrel on wheels, with a pump manned by volunteers, that sprayed water on the fire through a hose. This was complemented with bucket brigades if water was available near the fire. Barn and brush fires were more difficult to control and complete loss of the buildings or fields was usually inevitable. This was the case with Sandy Spring farmer Joshua Pierce who lost his barn in a fire in 1841 . He had not been able to afford fire insurance. His loss, however, did inspire the creation of the Incorporation of Montgomery Mutual Fire Insurance, which provided much needed affordable fire insurance and promoted fire safety and protection.

In the later part of the 1800s, a need for greater fire protection was beginning to be recognized. In 1873 the Rockville town commission purchased additional fire equipment and by 1887 waterworks and hydrants were set up in Rockville, making access to water easier. A group of volunteer firefighters was organized and two black citizens, George Meads and Dibby Herbert, used the two hand-drawn hose reels. George

Meads, “Chief’ of the little volunteer group, alerted volunteers with the shot of a pistol. Rockville had been receiving assistance from the District of Columbia Fire Departments but after a disastrous fire on Montgomery Avenue, the Rockville Volunteer Fire Department was formed. It took over the two hose reels and raised $3800 to buy a Model T. Waterous Ford triple combination pumper, which carried hose, water tanks and a pump. In 1931 Val Wilson formed a Rescue Squad and a rescue wagon was purchased which, in addition to being used for innumerable routine calls, responded to the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad crash that killed 14 school children when a train hit a bus.

Organization was also beginning to take place in Gaithersburg in the late 1880s as the town grew in response to the coming of the railroad and by September 1892, the town wanted a more formal fire organization. Six citizens were appointed to find a way and the means to organize a volunteer fire department, which they did immediately. A month later, the Volunteer Fire Company of Gaithersburg was responding to fires. There were, of course, no firehouses that housed on-duty firefighters of scheduled shifts for volunteers, and when the alarm rang all volunteers would come running. Eden Selby, who was the town barber around 1900, would drop what he was doing when he heard the church bells ring and run to duty, which would often leave customers with unique hairstyles unless they chose to wait in the chair for him to return. During the 1920s, fires destroyed much of Gaithersburg’s downtown – the Post Office, Etchison’ s Store, Brewer’s Real Estate offices and Thomas Hardware, Feed and Fertilizer- and in 1928 the present Gaithersburg-Washington Grove Fire Department was created by charter.

Meanwhile, in Takoma Park worries about fires were cause enough for one citizen to appeal in the Takoma Park News on October 11, 1890, for the organization of a trained bucket brigade with equipment. Unfortunately, the call went unheeded and in 1893 fire devastated the town, destroying Favorite’s Store, the Watkins Hotel, and Birch & Co. ‘s General Store. The afternoon of the fire, a committee was formed to organize a

fire company and in 1894 George L. Favorite was named first chief of the Takoma Park Volunteer Fire Department. Two weeks later the fire company acquired a hand-drawn, two-wheel hose reel with a gong hammer attached to one of its spokes. The local Boy Scouts trumpeting the call for help served as an early alarm system. In 1919 the fire company acquired the first Model T Ford pumper in the county and in 1922 was

incorporated. By 1928 a new firehouse, with a fa~ade covered by hundreds of river-bed stones from Sligo Creek, was completed at Carroll and Denwood Avenues.

Kensington, on the other hand, had a Fire Marshall shortly after the town was incorporated in 1894. In 1899 a fire destroyed the Town Hall and Montgomery Press building and all forms of fire protection were put under the control of a town Fire Marshall, who summoned volunteers to form bucket brigades and furniture salvage groups. The town provided their equipment, which consisted of a hand-drawn hose reel, a two-wheel chemical unit and several ladders. (Chemicals were mixed with water to create the pressure necessary to shoot water to the fire.) In 1916 volunteers were upset when the schoolhouse was burning and the Mayor would not let them tap into the town water to save it. By 1919 firefighter Eugene J.C. Raney had organized an independent group of volunteer firefighters from the town. Kensington Volunteer Fire Department was incorporated by the Maryland State Legislature in 1925 and later the town turned over control of its Ford Model T truck and hook and ladder truck.

The organization of these early fire departments in the county was mostly the result of destruction or death that made the communities realize what a threat fire was to their homes, businesses and livelihoods. In Silver Spring in the fall of 1914, when Sam Waters’ home on the south side of Sligo Avenue burned down, talk began about starting a volunteer fire department. In 1915, when nothing had resulted from the “talk” and the Silver Spring Post Office was destroyed by fire on May 5, the Home Improvement Club, a local women’s group, coerced their husbands and neighbors into action by setting up an organizational meeting at which the Silver Spring Volunteer Fire Company was created.

With 87 members at its inception, property was donated, membership dues taken, and votes were cast making Ike Oden the first fire chief The installation of water mains in Silver Spring, beginning in 1920, enabled quick access to water and made it unnecessary to leave a fire and go back to refill fire trucks with water.

In the early 1920s, it was recognized that some form of cooperation between the individual companies and the county needed to be established. Chiefs from the first five companies – Rockville, Gaithersburg-Washington Grove, Takoma Park, Kensington and Silver Spring – came together to form a Fire Board to serve as the link between the companies and the county government. The Fire Board allowed standards to be established countywide regarding equipment and water sources, but the individual fire companies continued to train their own volunteers and raise funds.

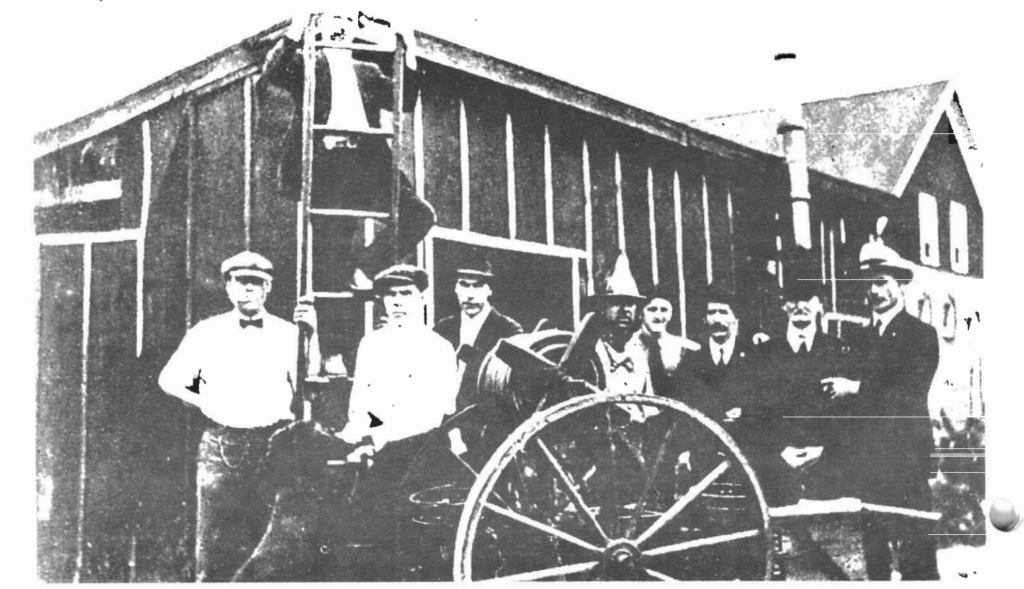

Silver Spring Fire Department – At Its First Firehouse, with Hose on Pull Cart

Another half dozen fire companies were formed in the county in the years between 1920 and 1930. The Sandy Spring Volunteer Fire Department was organized by 1924 with the support of the Young Men’s Club of St. John’s Episcopal Church, the Brookeville Post of the American Legion and residents A.D. Farquhar and Spence J.H. Brown. In 1926 the Bethesda Fire Department was organized and incorporated. A corps of 100 volunteers ran the department for thirteen years, until 193 9 when the Fire Board decided to hire nine fulltime men and a professional fire chief, Lt. Angelo J. Bargagni.

The volunteers responded by forming their own Bethesda Volunteer Fire Department, but some years later it closed down, leaving just the original fire department. The Chevy Chase Fire Department was the only fire department in the county not originally organized and run solely by volunteers. An Act of Legislature was passed defining tax areas to assess funds for fire protection and the Chevy Chase Fire Department went into service in February 1927 with six paid, fulltime men, led by Chief William F. Lanahan, and two dozen volunteers under Paul Grove and Robert Dunlop.

Silver Spring Fire Department with Chemical Tank and First Motorized Equipment

By 1954, however, the volunteers disbanded for lack of membership, leaving the fire department to be run by career firefighters. The Hyattstown Volunteer Fire Department was formed on May 21, 1929 by members of the community. Webster V. Burdette was elected President and the volunteers purchased a secondhand Ford truck and an International chemical truck. Through fundraising efforts, including annual Firemen Carnivals, turkey shoots, community suppers and various raftles, the fire department continued to add equipment to its fleet to better serve its citizens.

The Glen Echo Fire Department was organized in 1930 after a residential fire in Glen Echo took the lives of a mother and her four children. A firehouse was established with equipment and trained volunteers and by 1948, in response to community growth and the increase in calls, career firefighters were added. The Cabin John Volunteer Fire Department began with a meeting at Benson’s Store that was organized by Charles E. Benson and ten other volunteers on March 19, 1930. Originally established to “control, prevent, limit and combat damage by fire,” this fire department today also provides primary emergency medical services, river rescue services and heavy rescue in the Cabin John area and is home to a River Rescue and Tactical Services Team, which responds to all incidents involving moving water rescue throughout Montgomery County and the Potomac River.

In addition to the fire department volunteers donating their time, they have donated their own money from time to time, usually to purchase new equipment, but sometimes to cover the cost of a keg of beer and hot dogs. They also turned to their community to support their efforts in protecting local homes and businesses. Money has been raised by door-to-door collections, subscriptions, turkey shoots, carnivals, barbeque

dinners and card parties, selling Christmas trees, operating a bowling alley and presenting public entertainment. In 1918, when Silver Spring received a $5000 loan to purchase the Armory as their new home, volunteers began running carnivals down at the District Line, performing Minstrel Shows, and having an “Ugliest Man” and greased pig contests. Rockville got into the act in 1924 with entertainment geared to the male community, arranging an “Annual He Night” with boxing, wrestling and vaudeville.

The volunteer fire departments also served as social clubs for men and women alike. In many towns women began forming Ladies Auxiliary clubs shortly after the creation of the local volunteer fire department, as a means of showing support for the fire department. While most of these women were wives and daughters of firefighters, the auxiliaries were open to any woman in the community. The “Annals of Sandy Spring” states, “The Sandy Spring Women’s Auxiliary was begun with the idea that women in the community both near and far might be of service to the firemen at such time after a fire when coffee and food are needed, in assisting with the carnival and in raising money for the Department.” Dues were collected from members of the auxiliaries and their fundraising efforts were in the form of bingo games, card parties, dinners, lunches, flower shows, craft shows, etc. These funds were used to purchase kitchen equipment, fire fighting apparatus and hose, as well as food to be brought to the site of fires.

A few women were actually serving locally in fire protection in the 1920s. Rockville had its own Rockville Ladies Fire Company, organized in the mid-l 920s by Captain Alice Cashell Berry (Keech), a well-known county horsewoman. The Rockville Lassies, as they were called, raced to the fires just as the male fire companies did, but unless they arrived first their duties often consisted of looking after valuables, herding cattle at barn fires, and serving sandwiches and coffee. Captain Alice Berry recalled being in the middle of the street during a hotel fire in Rockville, carefully guarding someone’s bird and birdcage.

The Rockville Lassies were ready at the call of action and in one fire on Shady Grove Road the women did beat the men to the scene and had nearly put out the fire by the time the men arrived. Anyone could see the capability and commitment these women put forth when witnessed at hookup competitions, where they often took home several trophies. After being in existence five or ten years, the Lassies began disbanding as a result of marriages and children.

While fire departments depended primarily on fundraising efforts by the volunteers and women’s auxiliary, in the 1920s the towns, the county and the State of Maryland began helping support fire departments. In 1927 the Silver Spring Fire Tax District was established by the Maryland State Legislature to provide financial assistance through taxes assessed on residents in that district. By 1933 Maryland had passed legislation authorizing a fire tax and in Gaithersburg-Washington Grove the fire department was receiving ten cents from town residents and five cents from residents in the First and Ninth Districts.

Fire departments could also receive money from Montgomery County to maintain and upgrade apparatus and equipment. In 193 8 each fire department received a subsidy up to $1500, including $500 annually for each piece of equipment it maintained, not to exceed three. To qualify for this, the fire departments were required to have at least 1000 feet of hose or a pump or chemical tank. In addition, incorporated towns such as Rockville and Takoma Park were required to ask for appropriations from their own town council.

Early volunteers had little or no training in fighting fires, since equipment consisted only of buckets of water. As fire departments began formal organization, department chiefs became responsible for running drills and practices. According to the October 15, 1926, minutes of the Bethesda Volunteer Fire Department, Captain Dixon, who had recently retired from the District of Columbia Fire Department, was hired to

train firemen and canvas fire situations.

In 1933 at the first annual convention of the Montgomery County Association of Volunteer Firemen, firefighters from eleven volunteer departments attended the Fire College taught by Fire Marshal Sherwood Brockwell of Raleigh, North Carolina. Classes on such matters as how to safely remove a person from a burning building and proper methods on mounting a ladder were taught at the convention. The 1930s also brought the inception of the University of Maryland’s Fire and Rescue Institute. The September 2, 1932 issue of the Sentinel reported that Rockville’s firefighters were to take their third annual short course in firefighting, an intensive training session in modem methods.

By 193 7 Chief Angelo Bargagni, also formerly of a District of Columbia fire department, was establishing the first training school in Montgomery County, to be held in Kensington and Bethesda. In William Offutt’s “Bethesda: A Social History,”

firefighter Frank Hall recalls training with Chief Bargagni:

“They trained. I don’t care if it was 95 degrees in the summer of ’39~ they got out there, and they ran down that street, and they hooked up to that hydrant, and they charged that line … and they built a training tower. And they had to take that ladder out here, and he stood right out there himself and did all the training himself, and they had to take that line up that ladder in a certain way. Under your right arm and over your left shoulder. You had to take that line like that when you went in because you stepped off the ladder to the right of the widow and the hose came over the ladder and you got in, turned around and started pulling and then stuck that nozzle back out the window and said, ‘Charge the line.”

Bethesda Fire Department on Old Georgetown Road

Training also took the form of live fire demonstrations and hookup competition at the local fire department carnivals and county field days. Fire departments competed for trophies for speed and efficiency and the best-equipped department.

Between the years 1930 to 1940, the country was in the midst of the Depression and no new fire departments appeared in the county. In March of 1941, however, the County Commissioners approved the formation of the Hillandale Volunteer Fire Department. Membership reached up to sixty members that summer, the volunteers began acquiring equipment and a new firehouse was dedicated in 1946. On September 13, 1944, the Damascus Volunteer Fire Department was born when a handful of men met under a tree on the front lawn of Roscoe Purdum’s former home. Through various fundraisers, the volunteers and the Ladies Auxiliary raised enough money by 1946 to purchase a firehouse with two fire truck bays, a hose drying tower and a new fire truck. Next was the Upper Montgomery County Volunteer Fire Department, organized by the Monocacy Lions Club and members of the community. It was chartered in April 1946 by the five local communities of Barnesville, Beallsville, Dawsonville, Dickerson and Poolesville and by September of 1947 the fire department had its first fire truck.

The Burtonsville Volunteer Fire Department had its beginnings at a May 12, 1947 meeting at the Grange Hall that was attended by 45 men. During their first year the fire department answered only five calls, the first call being on November 1, 194 7, when the residence of Elizabeth Ruse on Greencastle Road was struck by lightning. A four-bay fire station was completed in 1949 and with the expansion came more equipment. Members of the Laytonsville community began organizational meetings in 195 2 and the Laytonsville District Volunteer Fire Department was open for business by the end of January 1954 with a 1930 Brockway fire engine. The county, however, did not acknowledge the department until they replaced their 27-year-old fire engine with a new pumper in 1957. Unfortunately, their building and equipment was all lost in a fire in 1963. Raising money by various means, they had a new home by March of the next year at a cost of $83,000.

In the summer of 1953 the National Institute of Health opened its Clinical Center and decided to organize the National Institute of Health Fire Department. Originally, only the Driver Operator and Assistant Fire Marshall were full time Fire Department employees and the remainder of the staff were volunteers from the Shops and Maintenance units. With additional staffby 1955, pickup and disposal of hazardous chemicals started. The Fire Department today is responsible for the entire National Institute of Health complex – 306.4 acres and 61 buildings. The firefighters receive specialized training in handling chemical, radiation, laboratories, infectious agents, bedfast and psychiatric patients, delicate instruments, research animals, etc. The Walter Reed Army Medical Center Fire Department is a Department of Defense Civilian Fire

Department that serves Walter Reed and the Forest Glen Annex. It protects primarily a residential area and tends to approximately 10,000 living in a three-mile radius, giving fire, emergency medical services, haz-mat, search and rescue, and extrication services.

Most of the nineteen fire departments in the county have just one station location, but the Rockville Volunteer Fire Department and the Kensington Volunteer Fire Department each have four stations and other fire departments have two or three. The Kensington Volunteer Fire Department, for instance, serves the Wheaton/Glenmont and the Aspen Hill areas as well as Kensington. As the need has arisen, fire departments have formed rescue and first aid groups, giving them special training and providing ambulances. In two instances, rescue squads

formed their own organization, completely separate from the fire department, with their own headquarters and memberships, while still assisting the firefighters in emergencies.

In the 1930s, the only ambulance serving the Bethesda area was the one housed with the Bethesda Fire Department and driven by volunteers. When Don Dunnington was suspended for driving the ambulance too close to the fire trucks, he and others formed the Chevy Chase First Aid Corps. Formally organized by a group of25 men and women in 1937, Dunnington and his group of Red Cross trained volunteers provided ambulance service to the fire department and handled emergency calls, routine transports and firstaid coverage at horse shows and baseball and football games. Two ambulances were purchased and Woodward & Lothrop donated linens and Peoples Drug Store donated first aid supplies. In late 1941, the Corps was disbanded due to a loss of volunteers who had joined our country’s armed forces, but when World War II ended in the fall of 1945 the group was reformed and was later renamed the Bethesda-Chevy Chase Rescue Squad. 22 Volunteers of the Kensington Volunteer Fire Department formed a similar rescue squad organization in Wheaton, chartered in 1955 as the Wheaton Volunteer Rescue Squad. The Wheaton Squad began with a 1950 ambulance purchased from the Bethesda Chevy Chase Rescue Squad.

Volunteers have joined firefighter units for many reasons and in the earlier days, they often joined for social enjoyment. Mickey Harris joined the Glen Echo Volunteer Fire Department in the early 1940s as a young man. “There just wasn’t much to do back then and people weren’t as occupied as they are today. It was just something you did since all the guys did it.” Things had not changed much by the early 1970s when Upper Montgomery County Volunteer Fire Department’s Ken Strite joined because many of his friends and neighbors were already members of the fire department. In addition to the personal satisfaction of helping save lives and property, the friendships he made in the fire department made it worthwhile. The number of hours spent on the job with fellow firefighters, in conjunction with the stressful situations that require trust and teamwork, lead to relationships on a different level than in an ordinary work environment. Strite recalled that when he was an active volunteer he knew all the other volunteers and their families. Down time at the firehouse was spent talking about everyone’s families, playing games and playing a lot of softball on the softball field adjacent to the firehouse. Days off would include family picnics and get-togethers with other volunteers.

Softball was often synonymous with volunteer fire departments in the years from the 1930s to the 1970s. It was popular and a perfect way to pass the time while waiting for the next call and many fire department men spent hours in a back lot or on their own softball fields. As the sport had little risk of injury and developed teamwork, departments organized teams and acquired uniforms. Rival departments would face off annually at the carnivals while vying for trophies. Aside from the Rockville Lassies of the 1920s, volunteer and career firefighters were always male. There was considerable “male bonding” among firefighters and women were considered totally unsuited to the physical and emotionally challenges of the job. Times changed, of course, and women did apply, but Bethesda Chevy Chase Rescue Squad’s first woman applicant, Lori Mackie, was rejected several times. Finally, the Montgomery County Fire Board did away with a policy restricting service in

operational fire/rescue positions to males, which was deemed to be in violation of county, state and federal equal rights laws. The first woman applicant was hired in 1976, Mary Ann Gollan, a 19-year-old newly married to a member of that Rescue Squad. Women who began joining the fire departments as volunteer and career firefighters in the 1970s did encounter some prejudices. Looking back, Firefighter Ron Barters recalled, “There was a bit of fuss since people didn’t think women could do the job. It had always been a man’s job … It definitely takes a certain type of woman to do it and want to do it.”

Some firefighters began their career at a very young age. Whether it was the influence of family members who were already part of a fire department or the idea of saving lives and dodging flames for a living, many firefighters could not imagine life without firefighting. Tim Bell from Rockville Station #3 began hanging around the Rockville station at the time of the Memorial Day Parade in 1979. He was thirteen years old when he started running errands and spending most afternoons and weekends helping out at the firehouse. When he was fifteen and a junior in high school, he joined the high school fire cadet program and was sponsored by the Rockville department. He spent half a day at high school in regular classes and then the rest of the day either training at the fire department or at the Academy. By age eighteen, while ta.Icing classes at Montgomery College, he was hired by the Rockville fire department as part-time casual labor. Years after he became a firefighter, his mother came across a photo of his great-grandfather, Henry Shelton, dressed as a firefighter and found out that Henry was chief of the allblack fire company in Rockville around 1915. 26

The firefighters of Montgomery County have included local farmers, merchants, community members and career firefighters of all ages and races in the 200-year history of our fire protection. Life as a firefighter, whether today or 200 years ago, means a commitment for the community, the saving of lives and property, interruptions in their daily lives and a bond with fellow firefighters.The duties and responsibilities of a firefighter encompass a variety of positions. Every firefighter must know how to run every part of the truck and do every job, as well as serving as educator, paramedic and fire prevention specialist. He or she must be a master of the use of hoses and nozzles, raising of ladders, and operating breathing apparatus, pumps and over 150 different tools. The needs of the community have expanded from fighting fires to preventing fires, handling hazardous materials, entering collapsed buildings – and rescuing cats from trees and children from bathrooms.

During the 1960s and 1970s several fire stations hired career fire and rescue workers as the number of daytime calls put pressure on volunteers and businesses. Jim Snyder stated that, “In those days [the early 1970s] there were more people working and living in town. They would just leave work. But then businesses said they couldn’t afford to let them go [when calls increased].”

In 1972 a Department of Fire and Rescue Services was organized, whose director was given authority over training for volunteer and career personnel, communications, and fire prevention. The struggle between the individual volunteer fire departments and the county persisted, the county wanting more governmental control and volunteers resisting. By January 1988 a County Council vote made career firefighters employees of the county.

Today the Montgomery County Division of Fire and Rescue Services oversees the development of the Division of Fire Prevention to enforce fire codes and investigate fires involving the loss of life or injury. The division of Operational Services is responsible for communications and administrative services for all fire and rescue services. The Training Division is responsible for the courses conducted at the Public Services Training Academy, which include a recruit school, firefighting refresher courses, emergency medical training and live fire courses.

In 1966 plans were made for a county police and fire training facility in the county. In 1973 the Montgomery County Training Academy opened on a 57. 7-acre site on Maryland State Route 28, where there is an academic building, a multipurpose fire training building and a control tower. The multipurpose fire training building has enabled firefighters to have first-hand, controlled fire experiences during the training process. Approximately five live fire classes are given each year with gas fires, at an average cost of $500-$800 for a few hours of bum. The multipurpose facility also contains many architectural features found in commercial, industrial and housing structures. Chop-out replaceable panels, sloping roofs, roofs with parapet walls, false elevator doors and openings, and a variety of window styles are incorporated to teach the firefighter the most efficient way to approach each feature. In addition, the Academy offers special training areas that include a metro rail car, liquefied petroleum gas, tankers, a flammable liquid pit, a cylinder and drum workshop, a natural gas workshop, a cave-in trench, and an electrical workshop, which draw firefighters from all over the state and country.

Montgomery County’s fire and safety standards have evolved into some of the highest standards in the state, with higher requirements and longer training hours for its firefighters than any other county. Basic standards are required for all beginning volunteer and career firefighters and advancement is dependent on continued education and experience. The Academy offers classes in volunteer orientation, entry-level fire fighting, emergency medical technician training, paramedic traininfi, career development courses and a weekly standardized training program for the field.

As the county population has grown and new needs arisen, many new special rescue groups have been created to be housed at, and run in conjunction with, the already established fire departments. One such group is the Special Evacuation Tactics Team, dispatched to respond to high angle rescues where ropes and rigging are the primary mode of rescue from cliffs and rocks. The Hazardous Incident Response Team, which responds to hazardous materials situations, and the Underwater Rescue Team, for rescue and recovery response, were organized in 1981 . The Montgomery County Collapse Rescue Team and Urban Search and Rescue, formed in 1985, are trained for response to trench accidents, building collapses, confined spaces, mass casualty incidents and urban victim search.

Firefighting today is a far cry from the days when there were bucket brigades formed of neighbors and family in time of crisis. Montgomery County now has over 900 career firefighters and 1000 volunteer firefighters. While each station receives financial support from the county, each station still depends on local fundraising. Ladies Auxiliaries no longer exist in our politically-correct society, but auxiliaries of men and women continue to support their fire department with fairs, dinners and bingos. Members of the community who have had property and lives saved have been eternally grateful to those who volunteer and those who choose to make firefighting their career. We can feel confident that today and into tomorrow, the Montgomery County Division of Fire and Rescue Services and all of the 33 fire and rescue stations will continue to grow and to meet the demands of the community in which they serve.

Text taken from “The Montgomery County Story,” Volume 46, Number 3 (2003) by Shannon Fleischer, published by Montgomery History”

Contact our Recruiter

Looking for information on joining a local volunteer fire/EMS department? search listings here or complete our short form below and our county recruiter will contact you, typically within 2-3 business days. You can also email recruiter@joinfirerescue.com